How systemic racism shaped the history of Canada's swimming pools

When it comes to swimming pools in Canada there's a long history of exclusion for people of colour.

Canadian pools were largely unsegregated in the early 20th century, unlike in America at the time. But people of colour were kept out nonetheless by official and, more often, unofficial channels.

For example, in 1923 the Edmonton city council passed a rule that banned Black people from swimming in city pools. The rule came after some white people and the Edmonton Exhibition Association, which opposed mixed bathing, complained.

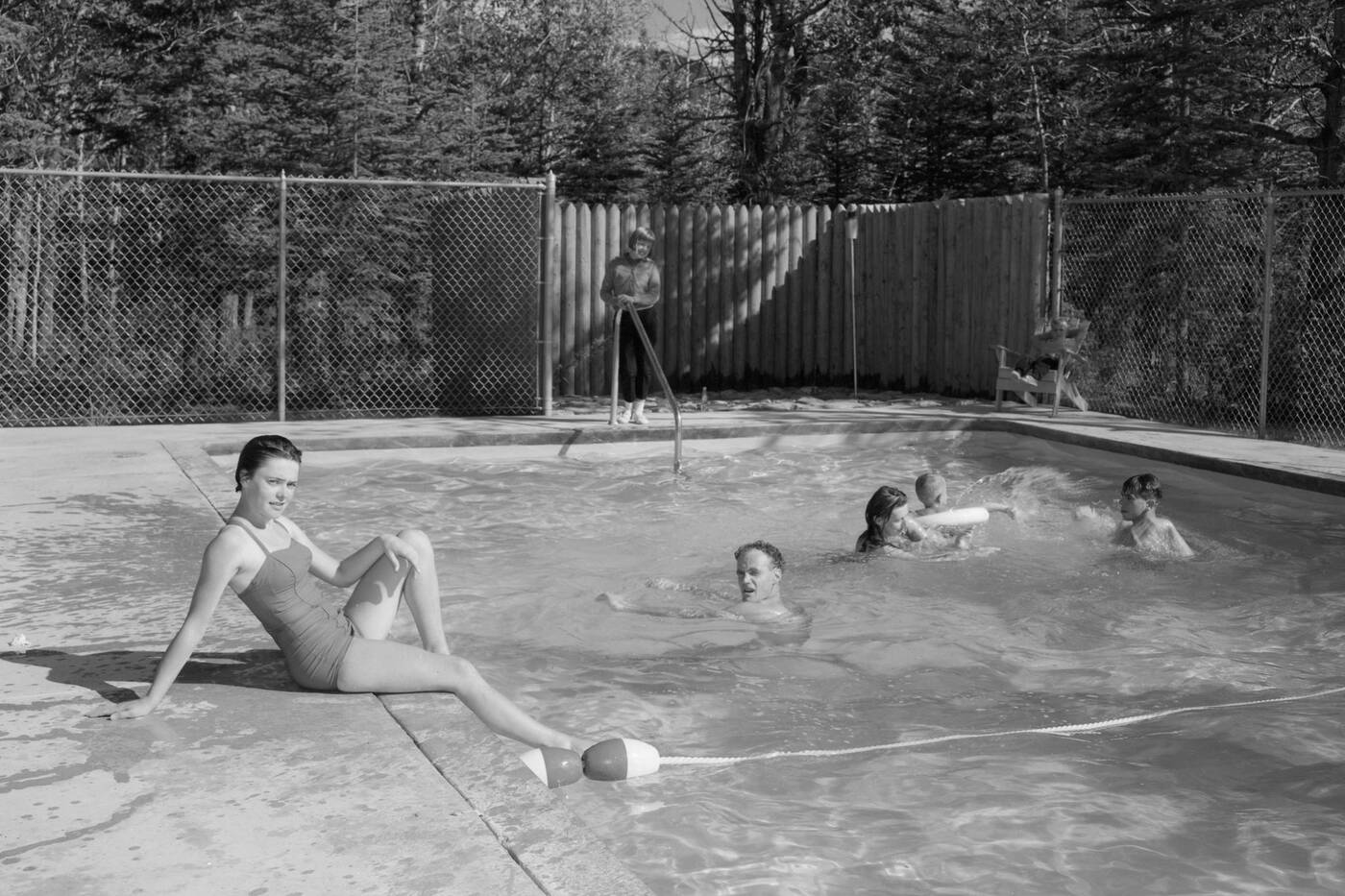

Swimmers relax by the Overlander Lodge pool near Jasper. Photo via Provincial Archives of Alberta

"Race was especially sustained as a category of discrimination in swimming spaces well into the twentieth century, especially as gender segregation faded away," explained Ornella Nzindukiyimana and Eileen O’Connor in an analysis of the Black Canadian social history of swimming between 1900 and 1960 published in the journal Society and Leisure.

In 1948, a Calgary pool manager refused to let a Black girl into his pool because of her skin colour.

In an article in the Calgary Herald, the manager said, "That's always been the rule here. If too many Negroes came to swim no one else would want to use the pool and we'd go out of business."

He said the rule also applied to Chinese and Japanese people.

"After all, the public makes the rules, and they wouldn’t stand for it. I have had complaints about Chinese and Negroes in the pool. So, I have to enforce this regulation in my pool," he told the paper.

Bathers enjoy the Sunnyside Pool in Toronto in 1929. Photo via City of Toronto Archives

Just one province over, Chinese children and their parents were banned from Vancouver's public swimming pool for six days a week between 1928 and 1945.

It's worth noting that while other racial groups often encountered racism in recreational spaces like pools, most recorded historical accounts in Canada focus on the experience of Black people.

However, regardless of race, racial segregation in Canada was often circumstantial, inconsistent and arbitrary.

For example, the Calgary pool manager also said that if the pool wasn't too busy people of colour could possibly be allowed in.

As Nzindukiyimana told Freshdaily in an interview, there were a lot of things that made it difficult for people of colour to feel welcome in public swimming pools – arbitrary rules being one of them.

"Discriminatory practices shifted on a whim. You never knew what to expect and it made it very difficult to navigate because there so many invisible barriers in your way," she said.

Swimming at Edmonton's outdoor pool in 1949. Photo via Provincial Archives of Alberta

On top of random rules, people of colour had to navigate the racially-charged fears of white people around swimming pools and beaches.

"Black people were kept away, in part because they were kept away from everything, but also water seems to trigger even more of a fear of mix of races," said Nzindukiyimana.

"As the century wore on and swimming gear (became) skimpier and skimpier people were scared white women would be exposed to the 'dangerous Black man.'"

Basically, interracial socializing at a swimming pool or beach was only slightly more tolerable than sexual intercourse and marriage, she said.

Nzindukiyimana added that there was also a fear of contamination.

"There was this notion that somehow, even if you were separated, that whatever disease they have would ooze out and contaminate the rest of the community," she said.

On top from racist attitudes there were also socioeconomic barriers that often excluded people of colour from the pool.

"As swimming developed into a sporting and leisure activity in the early 20th century, it quickly became white dominated," Nzindukiyimana explained.

Sunnyside Pool in Toronto. Photo via City of Toronto Archives

"It grew as a club sport (where) you need to pay to get in and it (was) a privilege. Swimming would often takes place in private, restricted venues, where Black people wouldn't be able to get in unless they worked there."

In other words, swimming was illustrative of a privileged social class position and thus inaccessible to many people of colour.

Even now swimming is still an expensive sport to take part in, which may in part explain the deficit of people of colour at the Olympic level.

However, Nzindukiyimana also told Freshdaily there's been decades of self-segregataion around swimming pools.

"After centuries of not doing something it becomes something that Black people don't do," she said.

Agreed! Unfortunately there’s a major correlation between Black people not being able to swim + segregation/racism which prevented our elders from accessing swimming pools + beaches.The lack of access then has led to a large % of our community still not knowing how to swim today.

— Shardé (@sb_pettis) August 11, 2020

And this idea that "Black people don't swim" means that even when they were seen swimming it was met with surprise, ridicule and resistance, to the point where people of colour often just avoid it all together so it didn't become "a thing."

"All you expose yourself to is being stared at and questioned," she said.

Nzindukiyimana also added that there was a fear around water that kept people from going to pools and beaches. This fear actually dates back to slavery.

As Nzindukiyimana explained, during times of enslavement Black people weren't allowed to learn how to swim, and were made to feel afraid of water. It was so slaves couldn't escape the plantations.

And this innate fear has transcended generations.

A study done in 2010 for USA Swimming found that one of the main reasons why Black children don't learn how to swim is because of their parent's fears.

"Fear of drowning or fear of injury was really the major variable," Carol Irwin, a sociologist from the University of Memphis who led the study for USA Swimming, told BBC.

Studies have also shown that if parents don't know how to swim there's less than a 20 per cent chance their kids will learn how to swim.

The result of years of historical exclusion from swimming pools and beaches means that, myths, such as the idea that Black people can’t swim because their bones are too dense, are still pervasive and present in modern day culture.

Sunnyside Pool in Toronto. Photo via City of Toronto Archives

And the pervasive racism has had knock-on effects.

Today, immigrants are less likely to know how to swim and ethnic minorities are at higher risk of drowning in Ontario.

Indigenous people are also disproportionately affected. According to 2016 Lifesaving Society data, between 2009 and 2014 about 10 per cent of the people who drowned were Indigenous, yet they make up only four per cent of the Canadian population.

But it doesn't have to be like that.

The Lifesaving Society has repeatedly called for swimming lessons to be a mandatory part of the school curriculum and research shows that participation in formal swimming lessons can reduce the risk of drowning by 88 per cent.

If learning to swim becomes a right of passage for children in Canada, we might be able to see drowning rates fall and, in the process, undo some of the effects that systemic racism and lack of pool access has had on people of colour.

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments